#14 China's Renewable Energy Transformation in Tibet Autonomous Region

Infrastructure and Strategic Implications

TL; DR

Renewables are now powering year-round habitation in TAR, dual-use infrastructure and the expansion of settlements into more permanent border towns.

Surplus power and expanding power corridors create scope for electricity exports to the geographical neighbourhood.

Renewable energy hubs in TAR appear to be scaling up fast. Still, environmental safeguards and protections for local culture/livelihoods are likely being treated as secondary priorities as build-out accelerates.

Renewable energy “Development” jobs often require specialised skills, so workforce inflows from other provinces can dilute local benefit-sharing and, over time, add demographic/cultural pressures.

1. INTRODUCTION

While the previous edition of the Geospatial Bulletin examined solar energy harvesting in the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) in depth, this edition turns to the other pillars of electricity generation on the plateau: geothermal, wind, and hydropower. The focus is not simply on where these projects exist, but on what they are designed to achieve: the scale of deployment, the stated purpose of these sites, the technological shifts enabling high-altitude operations, and the way infrastructure is being arranged and connected across TAR.

This assessment sits within a broader national context in which China’s renewable build-out has crossed a historic threshold. Total installed renewable capacity has reached 1,889 GW, accounting for 56% of the nation’s power capacity: wind and solar alone amount to 1,482 GW, overtaking thermal power at 1,451 GW. China also met its 2024 target of 1,200 GW of wind and solar six years ahead of the 2030 deadline announced by President Xi in 2020. By current estimates, China accounts for 44% of global renewable capacity and hosts approximately 64–74% of the world’s utility-scale renewable projects under construction. Against that scale, the TAR’s contribution is surprisingly modest: it holds less than 0.5% of China’s renewable capacity, about 7.176 GW out of 1,889 GW, roughly comparable to Austria’s solar photovoltaic capacity. Yet this small base masks a turning point: the region is now entering an acceleration phase, with substantial additions anticipated during 2026–2030.

Within TAR itself, the energy mix reveals an active contest between hydropower and solar. Rapid advances in solar panels and energy storage are helping solar expand quickly and compete more directly with hydropower, particularly in areas where grid upgrades and storage reduce concerns about intermittency. According to available data, the renewable energy breakdown is roughly as follows: hydropower ~53.7%, solar photovoltaic ~36.3%, and solar thermal ~1.4%. Other sources remain comparatively minuscule, wind nearly 3% and geothermal around 0.5%, but their strategic value is growing as developers push into higher altitudes and more remote locations. This competition could be decisively reshaped by the proposed 60 GW mega hydropower dam, which, if realised, would expand generation on a scale that could tilt the balance back towards hydropower for decades, particularly given its perceived reliability in meeting rising demand.

Official projections point to a potential steep change in TAR’s renewable trajectory. From a base of roughly 7.2 GW in 2024, capacity could rise to 9 GW in 2025 and 22.5 GW by 2030, lifting annual generation from around 17.5 TWh to approximately 70 TWh. The longer-term ambition is even larger: 100 GW by 2050 and 150 GW by 2060, with output increasing to approximately 350 TWh and 475 TWh, respectively. The strategy described in planning documents is an integrated portfolio in which the proposed Medog mega dam (60 GW) functions as the cornerstone, supported by expanding solar and wind capacity across the plateau. If Medog proceeds at scale, some projections suggest that TAR’s renewable energy capacity could reach about 210 GW by 2035, with annual generation nearing 750 TWh. Such an outcome would elevate TAR into a central clean-energy hub, reshape regional economic structures, strengthen China’s position on energy security, and accelerate the broader national transition through a combination of large-scale hydropower and solar build-out, expanded grid infrastructure linking interior settlements, and electrification of industrial and transport sectors.

These ambitions are reinforced by major transmission planning. A key element is the West-to-East power transmission programme, intended to move electricity from resource-rich western regions to energy-hungry eastern manufacturing centres. Targets under this approach envisage delivery of around 500 billion kWh annually to eastern hubs by 2050, a dramatic increase from the roughly 15.4 billion kWh transmitted since 2015. TAR’s future generation capacity becomes meaningful only at the national level if it can be distributed effectively; transmission corridors are therefore not a supporting detail but a central feature of the strategy: they link disparate renewable hubs, reduce curtailment risk, and turn remote generation into a system-wide asset. As renewable energy generation in TAR already exceeds local requirements, surplus electricity is increasingly transported to other parts of China. This infrastructure expansion also creates potential opportunities for electricity export to landlocked neighbours such as Nepal and Bhutan. Well-established transmission networks and abundant energy resources could enable China to offer competitively priced electricity to these countries, with significant strategic implications for India’s regional energy diplomacy and economic influence.

These ambitions are reinforced by major transmission planning. A key element is the West-to-East power transmission programme, intended to move electricity from resource-rich western regions to energy-hungry eastern manufacturing centres. Targets under this approach envisage delivery of around 500 billion kWh annually to eastern hubs by 2050, a dramatic increase from the roughly 15.4 billion kWh transmitted since 2015. TAR’s future generation capacity becomes meaningful only at the national level if it can be distributed effectively; transmission corridors are therefore not a supporting detail but a central feature of the strategy: they link disparate renewable hubs, reduce curtailment risk, and turn remote generation into a system-wide asset.

Against this backdrop, the sections that follow offer a spatial analysis of TAR’s renewable infrastructure beyond solar, and examine geothermal, wind, and hydropower, where capacity is being concentrated, how projects are being networked through transmission, and how these developments may influence the plateau’s internal settlement patterns, industrial priorities, and the broader geopolitical environment around the Himalayas.

2. GEOTHERMAL ENERGY

The Himalayan Geothermal Belt (HGB) stretches over 3,000 km from Pakistan to Myanmar and Thailand. Formed by the Indian–Eurasian plate collision, it concentrates high-temperature fields along the Yarlung Tsangpo fault zone, where crustal deformation and elevated heat flow sustain extensive hydrothermal systems.

In terms of footprint, the region is home to two operational geothermal plants - Yangbajing and Yangyi. While Yangbajing is the most widely known geothermal site in the Tibet Autonomous Region, the exact locations of several other geothermal fields and operational stations are not publicly disclosed. At the same time, the region also features tourism facilities centred on hot springs, indicating that geothermal resources are used not only for energy and research purposes but also for recreation and visitor-oriented activities. Yet, the plateau stands out as a mesmerising geyser basin, home to approximately 672 active geothermal zones. Among these, 34 zones exhibit remarkable potential, surpassing 150 °C.

It’s fascinating to note that not all these geothermal features are suitable for exploitation. The variety within these zones is striking, ranging from steam vents and destructive hydrothermal explosions to bubbling hot springs, with many sources exceeding 80 °C.

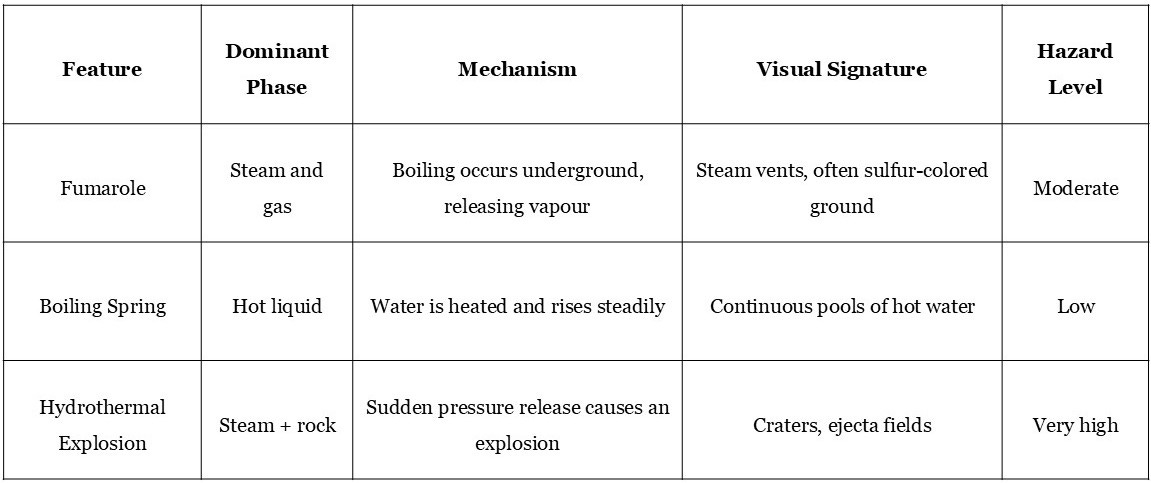

Table 1 illustrates the differences between various types of geothermal resources in TAR.

In summary, fumaroles represent dry steam venting, boiling springs represent steady hot-water flow, and hydrothermal explosions represent catastrophic steam release. They form a continuum reflecting increasing instability and pressure within geothermal systems.

The Yangbajing region near Lhasa in TAR is one of the world’s most extensively studied geothermal fields. A fault-bounded basin beneath the majestic Nyainqentanglha mountain range characterises this system.

The geothermal reservoir comprises two distinct units: a shallow reservoir located at depths of approximately 180 to 280 meters and a much deeper reservoir that reaches depths of around 5 kilometres. The heat that fuels this system is derived from a cooling magmatic body within the fractured granitic rocks of the Himalayas.

Geochemical and isotopic studies have provided compelling evidence that meteoric water precipitation that infiltrates the ground percolates through the extensive network of faults in this region. As these waters descend, they are subjected to increasing temperatures and pressures, which cause them to heat further with depth. Eventually, this heated water rises to the surface, contributing to the region’s notable geothermal features, including hot springs and fumaroles.

The unique geological and hydrological dynamics in Yangbajing highlight the complexity of the geothermal systems in this area and have significant implications for scaling geothermal as a sustainable energy source in this high-altitude environment.

2.1 Is this a new plant developed in response to China’s recent renewable energy push in the TAR?

The answer is “no”. Commercial activity began in 1977 with the establishment of China’s first high-temperature geothermal plant at Yangbajing, which had an initial capacity of 1 MW. Between 1981 and 1991, eight additional units, each with a capacity of 3 MW, were added. Later, in 2009-2010, two screw-expansion generators with a capacity of 2 MW were introduced, bringing the total capacity to approximately 26 MW.

Several medium- and low-temperature systems, including Dengwu, Huitang, Langjiu, and Naqu, were ultimately decommissioned due to a combination of factors. These systems faced significant challenges, including poor economic performance that made them unsustainable, persistent scaling issues that hindered their operational efficiency, and modest thermal efficiency that failed to meet industry standards. Consequently, their inability to deliver optimal performance led to their decommissioning.

Regarding utilisation, while reservoir characteristics technically limit power generation, direct applications are diverse. These include greenhouse and space heating, balneology (the study of therapeutic baths), medical uses, and industrial washing. During the 13th Five-Year Plan (2016–2020), policies encouraged the exploration of Hot Dry Rock (HDR) resources in southern Tibet, indicating a shift toward deep-heat extraction. Concepts for Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS), which utilise fracture-controlled reservoirs, have also been proposed for areas like Yangbajing and Gulu.

In recent years, extensive research has been dedicated to sustainably harnessing geothermal potential. A significant initiative aimed at this goal is the effort to interconnect isolated electricity grids, which will facilitate the connection of remote power generation sources and ensure energy distribution to locations with limited access to electricity, even reaching some of the most distant areas.

Notable projects include the Qinghai–Tibet Networking Project, launched in 2011, which successfully integrated Tibet’s 500 kV electricity network with the national grid. This ambitious initiative was bolstered by the establishment of 16 strategically positioned substations, enhancing the efficiency and reliability of electricity transmission across the region.

Another groundbreaking attempt is the Qamdo–Shenzhen Ultra High Voltage (UHV) transmission initiative, slated for completion in 2025. This project aims to transmit approximately 10 gigawatts of renewable energy, derived from geothermal, hydro, and solar sources, over an impressive 2,681-kilometre distance to the Greater Bay Area. This initiative is projected to reduce carbon emissions, offsetting around 12 million tonnes of coal annually, contributing significantly to environmental sustainability, and supporting China’s 2060 Carbon net-neutrality mission.

2.2 Is geothermal energy extraction a safe practice?

The process’s safety profile is complex and warrants careful consideration, particularly the management of geothermal fluids. Incomplete reinjection of these fluids, which are frequently enriched with minerals such as boron and fluoride, has led to localised soil contamination and increased sedimentation risks in vulnerable Tibetan alpine ecosystems. This situation highlights the necessity for robust environmental safeguards. Key priority measures to mitigate these risks include implementing comprehensive reinjection protocols, enhancing waste-stream management strategies, and exploring selective hybridisation with solar energy technologies. Such integration can optimise the performance of geothermal plants while minimising their environmental footprint.

Furthermore, with diligent reservoir management and strict adherence to environmental compliance standards, Tibet’s geothermal resources have the potential to advance a low-carbon energy portfolio significantly. They can complement existing hydropower and solar systems, meet local heating demands, and bolster grid stability. However, any efforts to scale up geothermal extraction must be cautiously approached, as they may pose serious environmental challenges and profoundly affect local communities. A new geothermal facility has been successfully established in Nagqu at an altitude of 4500 m. By overcoming two significant challenges, this facility has successfully tapped Nagqu’s geothermal resources, ensuring stable system operation. As a result, it now provides heating to nearby urban areas in Nagqu for 7 months without interruption.

Notably, the economic viability of geothermal energy remains a critical concern. Despite its potential benefits, it is still regarded as one of the less favoured renewable energy resources for utility-scale extraction, primarily due to upfront costs for exploration, drilling, infrastructure, and ongoing management expenses. These financial challenges can hinder large-scale deployment despite the long-term advantages.

WIND ENERGY

China has reported remarkable growth in wind energy capacity within the TAR over recent years, reflecting a significant commitment to renewable energy development in this challenging environment. In 2023, TAR added a substantial 700 megawatts (MW) of wind power capacity by completing 11 projects. This momentum continued into 2024, when the region expanded its capabilities by an impressive 860 MW from 15 additional projects. The upward trajectory of wind energy development accelerated further in 2025, with the area seeing a notable increase of 2,600 MW attributed to just two large-scale initiatives.

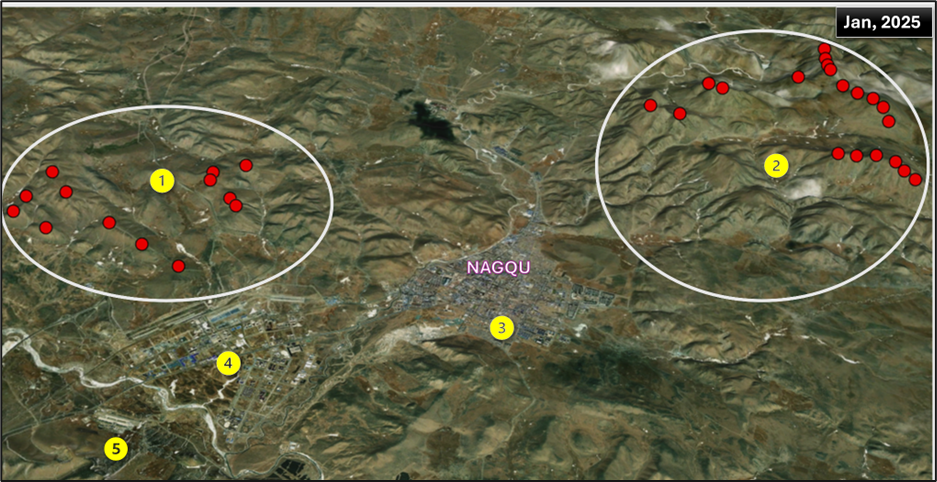

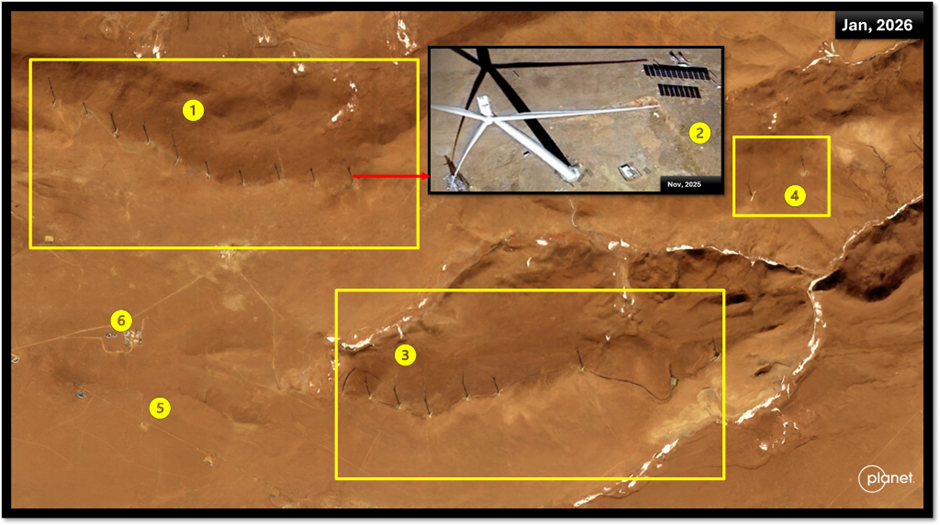

Label 1 marks part of the Omatingga Wind Power Project, while Label 2 points to another wind project in the Nagqu area. Both sites are located at altitudes above 4,500 metres, highlighting the development of wind power in extreme plateau conditions. Label 4 indicates a military zone, and Label 5 appears to mark a heliport inside or close to that zone. Given the proximity, it is plausible that the army facilities could draw electricity from the Omatingga wind site (Label 1), either directly or through the local grid. At the same time, Nagqu city is more likely to rely on power from Site 2, along with additional supply from a solar farm south of the town, suggesting a combined wind–solar energy base supporting civilian demand. Among these projects, the Omatingga Wind Power Project near Nagqu City stands out as a landmark installation. Commissioned in early 2024, this facility boasts a capacity of 100 MW. It operates at altitudes ranging from 4,500 to 4,800 meters, earning the title of the world's largest high-altitude wind farm at the time. The project incorporates nearly 25 wind farms, each with a capacity of 4 MW, spread across an area exceeding 140,000 square meters. It is projected to generate slightly over 200 million kilowatt-hours of clean electricity annually to sustain around 200,000 residents, thereby presenting a significant boon to local energy resources and contributing to environmental sustainability.

In October 2024, according to the media claims, another key facility commenced operations in Baxoi County in eastern TAR. This installation features 20 advanced wind turbines with a total capacity of 100 MW, each standing at an impressive 5,305 meters. This positions it as the world’s highest wind farm. The design and engineering of these turbines have successfully addressed various classical challenges, such as blade stall, ensuring optimal performance even under extreme conditions. These turbines are building resilience against low temperatures, intense ultraviolet radiation, and frequent thunderstorms, thanks in part to nationwide efforts initiated in 2019 that established standards for high-altitude wind turbines, intended for installation at 2,000 meters and above. These standards focus on achieving stable operations and ultra-high efficiency, like in other previous projects.

In addition to standalone renewable energy initiatives, several integration projects are currently under development to enhance the efficiency and reliability of energy production in the region. A noteworthy example is the Sakya Wind and Solar Integration Project, spearheaded by CNNP (Chinese National Nuclear Power) Rich Energy Co Ltd. This ambitious project is now in its final debugging stage and is set to commence operations within this month. Once operational, it is projected to generate 300 MW of renewable energy, with wind power contributing 200 MW through the installation of 40 state-of-the-art turbines, each with a capacity of 5 MW. This significant output is expected to yield over 600 million kilowatt-hours (kWh) of clean energy annually, helping meet the region’s energy needs. Current reports indicate that the installed capacity of solar and wind power in the area has exceeded 9,000 MW, with solar energy accounting for the predominant share. However, the wind energy sector is rapidly gaining ground, reflecting a growing commitment to diversifying energy sources.

3.1 Technological advancements

High-altitude wind farms in TAR have expanded faster because China has developed technology made for plateau conditions. Site selection employs advanced wind resource mapping and computational fluid dynamics modelling to study wind behaviour in complex mountain terrain, select the best sites, and estimate the electricity each location can produce before construction begins. This reduces trial-and-error and helps design wind farms more efficiently.

Chinese turbine makers have also improved equipment to work in thin air, extreme cold, and sudden weather changes. Turbines are fitted with better stability and control systems so they can run smoothly even when winds shift quickly. Key parts are strengthened to handle hail, lightning, and heavy wear from wind, dust, snow, and ice. Cold-weather features such as heating, moisture control, and upgraded insulation help prevent failures, while improved lightning protection reduces damage during storms. Developers also use stronger blades and more durable surface coatings so the turbines last longer in harsh conditions.

Just as important, China has improved the “support system” around these wind farms. Remote sites are monitored using sensors and remote diagnostics, enabling faults to be detected early and repairs to be planned quickly. Before a wind farm starts operating, every turbine is carefully tested, and the entire electrical system is checked and appropriately connected to the nearby grid infrastructure. Better transmission links and grid management have made it easier to transmit electricity from remote parts of TAR, which is essential for turning strong plateau winds into usable power.

3.2 Do these wind farms only bring power?

The establishment of wind farms in remote regions can expand electricity generation capacity and, when integrated with broader grid systems, improve electricity supply. Beyond power, these projects also support job creation and the development of technical capabilities for renewable-energy operations. Each wind turbine can require around 8 to 10 qualified technicians and workers for a range of operational activities, including monitoring, maintenance, repairs, and related logistics. However, while renewable energy infrastructure expansion and associated urban development may create new employment opportunities in TAR, many of these positions tend to require skilled labour in specialised fields such as electrical engineering, turbine maintenance, and grid management. As a result, a portion of these roles may be filled by workers brought in from other Chinese provinces rather than local Tibetan populations, particularly where access to relevant technical training and certification is limited. Although such employment trends are often presented as economic development for the region, the distribution of benefits may not be uniform across communities and, in some contexts, can contribute to demographic and cultural pressures. At the same time, project proponents and official narratives frequently claim that job inflows contribute to socioeconomic development and that exposure to large-scale renewable projects can support the growth of a workforce more familiar with advanced technologies and modern energy practices—though the extent of local participation may vary across locales and policy designs.

Enabling these wind farms in challenging terrain has required significant investment in supporting infrastructure and exceptionally robust transport networks. Good-quality roads have enabled the transport of extremely long wind turbine blades, close to 90 metres in length, and large components such as hubs and tower sections, often moved from manufacturing sites over 1,000 kilometres away. This improvement in connectivity has practical implications for construction timelines and for the ongoing operation and maintenance of wind facilities, including the movement of heavy equipment, spare parts, and technical personnel. It also highlights the broader role of enabling infrastructure in determining where high-altitude wind projects can be built and maintained at scale, and how quickly they can be expanded in remote areas.

Overall, the wind energy initiatives in TAR reflect China’s broader strategy to expand renewable generation into high-altitude and remote areas. In policy terms, these projects can help diversify the regional energy mix and support emissions-reduction objectives, particularly when paired with transmission capacity and complementary sources such as hydropower. They also coincide with infrastructure build-out and the diffusion of technical systems into areas that have historically faced logistical constraints. At the same time, the socioeconomic effects are not uniform. They may vary across localities, depending on workforce availability, access to training, procurement decisions, and the extent to which local communities are integrated into construction and operations. As such, the wind build-out can be read as both an energy-transition initiative and a development intervention, with outcomes shaped by implementation choices as much as by installed capacity.

4. HYDRO ENERGY

TAR’s hydropower journey began in 1959 with Ngachen Station (7.5 MW), but growth remained modest until the 2000 ‘Great Western Development’ initiative. The pioneering plant, with an initial installed capacity of merely 7,500 kilowatts and powered by six generators, marked a significant historical milestone, powering TAR’s capital with electric lights for the very first time.

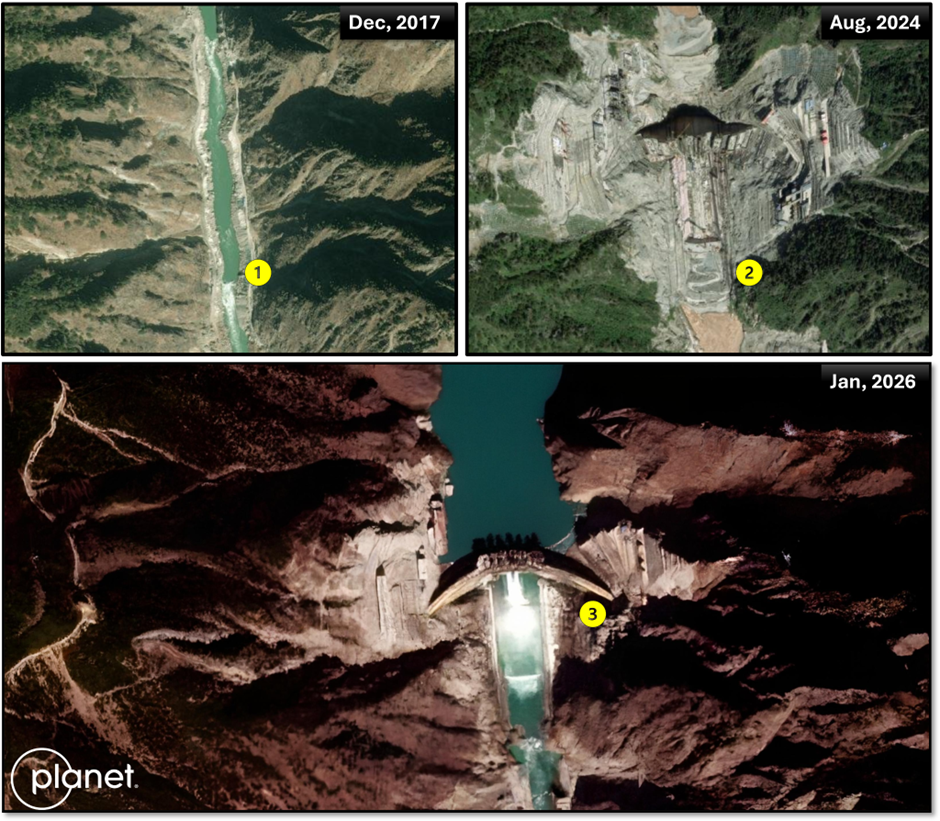

This initiative catalysed an unprecedented pace of hydro project development in TAR. Particularly in the past decade, the region has witnessed remarkable advancements. The deployment of cutting-edge technology to build high-performance, efficient dams is gradually overcoming previous limitations. One of the most ambitious projects on the horizon is the planned construction of the world’s largest hydropower project in the lower reaches of the Yarlung Tsangpo River. With a staggering capacity of 60,000 megawatts, this project will dwarf China’s current largest dam. The significance of this venture extends beyond sheer scale; it is set in a region characterised by environmental fragility and a high susceptibility to natural disasters such as landslides and earthquakes. Despite these challenges, proponents of the mega dam project assert that it will not adversely affect downstream regions in India in terms of water flow or environmental degradation, an assertion that remains sceptical. Additionally, the ambitious plans include the development of five cascading dams on the Motu River, capitalising on an elevation drop of over 2,000 metres across a short span of less than 50 kilometres. This ingenious design is projected to generate an astounding 300 billion kilowatt-hours (300 TWh) of electricity annually.

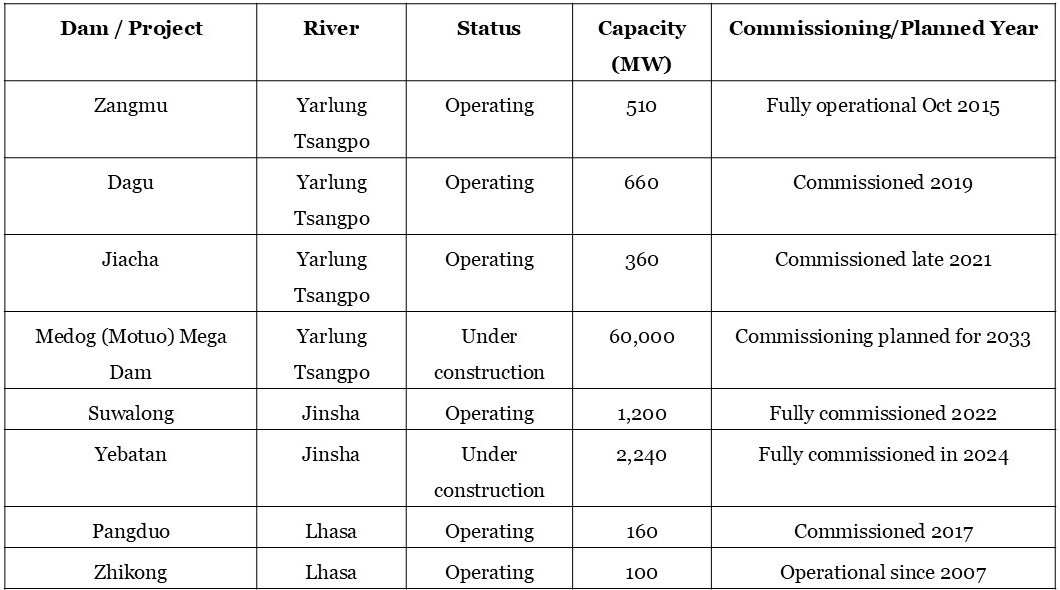

Table 2 lists key hydroelectric projects in the Tibet Autonomous Region.

This study examines a few hydropower projects shown in figures (4-7) across three major river systems in the TAR. These rivers originate in high-altitude, glaciated mountain ranges at elevations above 5,000 metres and flow through deep valleys and gorges. Their hydrology is primarily shaped by glacial melt and monsoon rainfall, resulting in strong seasonal flows and significant energy potential.

The Yarlung Tsangpo and Lhasa rivers lie entirely within the TAR, while the Jinsha River forms much of the eastern boundary between Tibet and Sichuan before joining the Yangtze system. Together, these river systems support an extensive hydropower cascade, ranging from small run-of-the-river stations to the planned Medog hydropower facility, which is set to be the world’s largest.

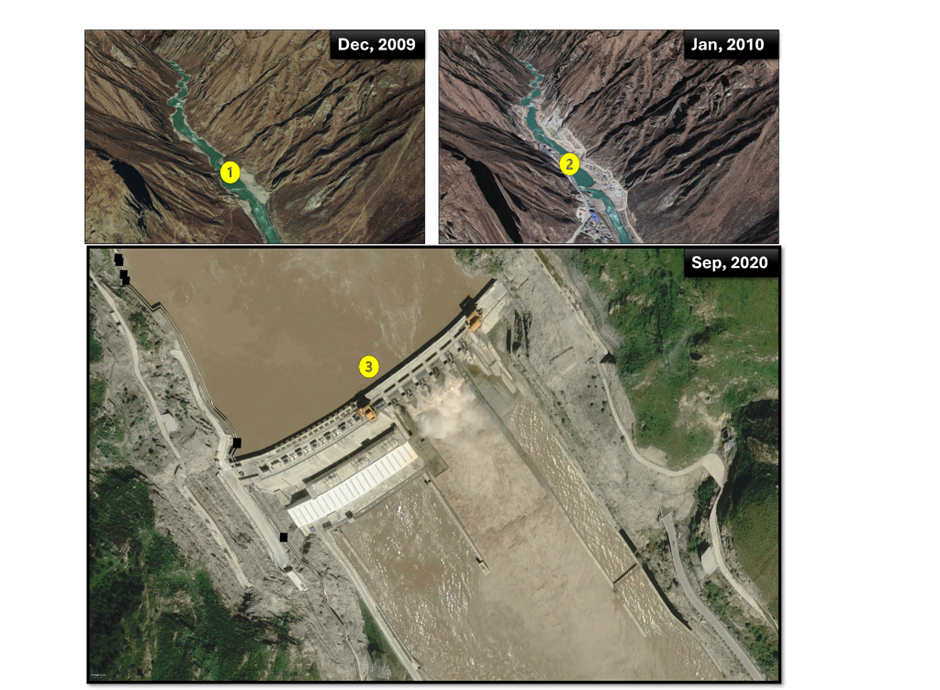

Although the Yarlung Tsangpo has been examined in detail in earlier studies, this section focuses on the main hydropower projects along its course and tributaries as the river descends from high altitudes into narrow canyons. Key tributaries include the Lhasa, Nyang (Niyang), Nianchu, and Laka Zangbu rivers. One of the most prominent projects is the Zangmu Dam, a run-of-the-river facility with a capacity of 510 MW and an annual generation of about 2.5 billion kilowatt-hours. Most projects on this system follow a similar run-of-the-river model, with only limited storage. Other operating projects include the Dagu Hydropower Plant in Sangri County, commissioned in 2023 upstream of Zangmu, and the Jiacha Hydropower Project in Jiacha County, commissioned in late 2021 downstream of Zangmu. Major projects under construction include Jiexu and the highly anticipated Medog (Motuo) project, alongside several smaller planned installations. Close to 10 projects, ranging in scale, are operational, under construction, and planned in Yarlung Tsangpo.

The Jinsha River system originates in the Tanggula Mountains on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau at elevations above 5,000 metres. Its headwaters form the Tongtian River, which flows southeast before becoming the Jinsha River near the Tibet–Sichuan border. For more than 400 kilometres, the Jinsha serves as a natural boundary between Tibet and Sichuan, cutting through deep gorges in eastern Tibet and western Sichuan. Key projects along this stretch include the Suwalong Hydropower Project, operational since 2022, and the Batang Dam, operational since around 2020. Large projects such as Yebatan, Lawa, and Changbo are under construction, alongside numerous smaller water conservancy schemes.

The third major system discussed is the Lhasa River, which originates on the southern slopes of the Nyenchen Tanglha Mountains near Lake Namtso at elevations between roughly 5,000 and 5,300 metres. Formed by the convergence of three smaller rivers, the Lhasa River flows through deep valleys in its upper reaches before turning southwest and passing through Lhasa city. It runs for about 450 kilometres before joining the Yarlung Tsangpo. Important hydropower projects on this river include the Pangduo Dam, with a capacity of 160 MW, commissioned in 2017, and the Zhikong Dam, a 100 MW facility operational since 2007. In addition, several smaller water conservancy projects are distributed along the river.

Overall, these three river systems form the backbone of hydropower development in the TAR. Beyond these, numerous dams and smaller conservancy projects are also present across western and central Tibet, reflecting the region’s growing role in China’s high-altitude hydropower strategy.

5. WORLD-RECORD CLAIMS: VERIFICATION AND REALITY

In 2025, China’s Tibet Autonomous Region was widely recognised as a frontier for “world-record” renewable energy. Some of this narrative holds up, particularly with projects like the Caipeng solar-plus-storage installation at 5,228 meters, the Zabuye concentrated solar power (CSP) project at approximately 4,500 meters, and the Qonggyai wind project, reportedly reaching 5,370 meters. These projects are well-documented as exceptionally high-altitude deployments.

However, the broader claims about records begin to falter upon closer inspection. Many impressive figures, such as annual energy generation, the number of households powered, emissions reductions, construction speed, and specific engineering details, are often based on project announcements rather than independent verification. Additionally, at least one wind power record claim lacks clear corroboration from accessible third-party sources. Even when the underlying technological advancements seem genuine, like the very large impulse turbine units developed by Datang Zala, phrases such as “world’s first” can sometimes be more promotional than officially validated.

While the Tibet Autonomous Region is plausibly emerging as a testbed for extreme-altitude renewable energy, only a subset of its claimed “world records” can be confidently asserted without careful qualification.

6. PARTING SHOT

China’s push in the TAR suggests a clear intent to draw on every available renewable source to advance its 2060 carbon-neutrality goal while accelerating regional development. In practice, this translates into rapid electrification to support the modernisation and urban growth of Tibetan towns, enabling a larger and more permanent human footprint in a harsh environment. Reliable, abundant power also underpins industrial expansion and resource extraction, turning electricity into a lever for reshaping TAR’s economy and land use. Crucially, the build-out is not confined to local consumption: surplus generation is channelled eastwards to industrial centres through new high-capacity transmission corridors designed to move power over long distances with minimal loss. Several grid projects are underway along multiple routes, linking distinct renewable hubs into an integrated system intended to capture and export the region’s energy potential. Over the years, a powerline network has been established across the TAR, with a higher density in the central and southern parts. This network increasingly connects major renewable energy sources with population centres, including remote areas. More than 90,000 electricity towers/poles are already present in the region, and the number continues to grow, underscoring the systematic expansion of electrification in the TAR.

These gains, however, come with costs that are too often treated as secondary. While the electricity produced is low carbon, the construction footprint, roads, blasting, tunnelling, reservoirs, foundations, and transmission towers can be environmentally disruptive, and operational impacts may alter hydrology, habitats, and fragile high-altitude ecosystems. Social consequences are equally visible. Local opposition has not consistently slowed flagship projects, and relocation pressures have accompanied major developments.

One such example, we studied earlier, is the displacement linked to the Yangqu dam expansion on the Machu River, including the submergence and possible relocation of the historic Atsok Monastery, which illustrates how cultural heritage and livelihoods can be placed at risk when infrastructure priorities dominate.

While hydroelectricity generation on the Yarlung Tsangpo carries direct downstream implications for India through potential flow regulation and dam-cascade effects, other renewable energy sources—geothermal, wind, and solar—do not directly affect India. However, these projects are strategically crucial for India.

Renewable energy infrastructure enables sustained human presence in previously remote, sparsely populated areas near contested borders. For example, small-scale solar plants are already providing power to remote border regions, as discussed in the previous edition. Additionally, wind farms at Chigu Lake are located approximately 80 km from the international boundary and 150 km from Tawang, Arunachal Pradesh, India. The expansion of transmission networks and electrification is transforming small and medium-sized border towns into more permanent urban settlements. A reliable electricity supply supports year-round habitation, the expansion of military facilities, dual-use infrastructure, tourism and other economic activities in regions that have historically been difficult to settle and administer. This gradual urbanisation and infrastructure densification near sensitive border areas, enabled by abundant renewable energy, represents a form of strategic presence that extends beyond the immediate technical function of power generation. Taken together, renewable energy in TAR is better understood not as a simple “green transition”, but as a strategic programme combining engineering ambition, grid integration, industrial policy, and state capacity – one that will continue to expand and, by its scale and geography, carry implications beyond China’s borders.

Latest updates from the Geospatial research group:

New in the newsletter: “Geospatial Snapshots” 🗺️ — brief updates, big picture.

Read “Iran at a Tipping Point” latest story map for a geospatial look at what’s shifting on the ground.Our latest book chapter is out: “Geospatial Governance in a Global Context”.

Authored by Dr Y. Nithiyanandam and Swathi Kalyani, it is published in Global Land–Ocean Geospatial Applications: Mapping and Surveying with Remote Sensing and GIS (CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group).

For regular updates on our geospatial research, stay tuned to https://takshashila.org.in/geospatial-research.

Acknowledgement: The author thanks reviewers for giving constructive feedback on the report.

Disclaimer: Please be aware that the information and opinions provided in this newsletter are intended for informational purposes only. We advise readers to exercise their judgment and consider multiple sources of information before drawing any conclusions or making decisions based on the content presented in this newsletter.

Declaration: This article has been proofread using AI tools.

For more products from Takshashila Institution, refer to: https://takshashila.org.in/newsletters/